I wasn’t born in Stonehouse, but I think I am a Stonehouse person. I wasn’t even born in Gloucestershire, but I am a Gloucestershire person – ‘If I do want, I can tellee, sna?’. I didn’t reach Gloucestershire until 1939. My grandfather, Arthur Peters, wasn’t born in Gloucestershire either, but he lived here from the age of ten until his death in 1938.

Arthur Peters married Amy, a girl he met at school, and they went to live at Highgrove Lodge, on the A433, where she was the gate opener. Later they moved to a hamlet called Upton Road. His father had apprenticed him, at the age of 13, as an ironmonger, working for a Mr Witchell in a building which had been the coaching inn, the Three Cups, that appears in Jane Austen’s Northanger Abbey. He stayed in the job all his life but mainly worked as a blacksmith. Many farm railings south of Stroud were put up by him. He was very keen on gadgets: he built his own home gasworks, and from time to time he bought things at auction. I have been told that all Peters men wave their hands about when they are talking. He certainly once bought an armchair by accident, and possibly the missing Constable, but that’s another story.

Arthur and Amy’s first home was Highgrove Lodge, A433 at Doughton

Then they moved to Upton Road

Mr Witchell’s blacksmith shop

Grandpa was a chronic joiner. He became a member of the rifle club and the Volunteers. He was called up for the army in the very late conscription of 1916, though he failed his medical for reasons that were never explained; but as a Volunteer he spent one day a week during the war guarding Quedgeley with the rifle he kept in the pantry under the stairs. He joined the Antediluvian Order of Buffaloes; and he joined the congregation in every pub in the area, especially the Greyhound and the Crown. At the Crown he met a group of men who came to the pub only once a week because they worked so far away. They became friends.This is the proper history bit: we know, don’t we, that a servant once chucked a couple of pints over Sir Walter Raleigh because he thought his master was on fire, even if we found the story in a Ladybird book. Raleigh is credited with beginning the habit of smoking in Britain and Ireland. Soon after that, someone discovered that tobacco would grow in Gloucestershire. It was becoming quite a serious industry, until the so-called Virginia lobby in Parliament managed to protect the plantations they owned by making tobacco growing illegal in England. But somehow the law didn’t always apply strictly to rich people, who often cultivated a little Nicotiana plant or two in their hothouses along with the pineapple: ‘For my own personal use, officer’ as people are sometimes quoted.

The blacksmith, alleged to be a picture of young Arthur at work

The Chipping railings. The authorities had worried that when the pubs closed, happy men might fall on to the new road which had been excavated.

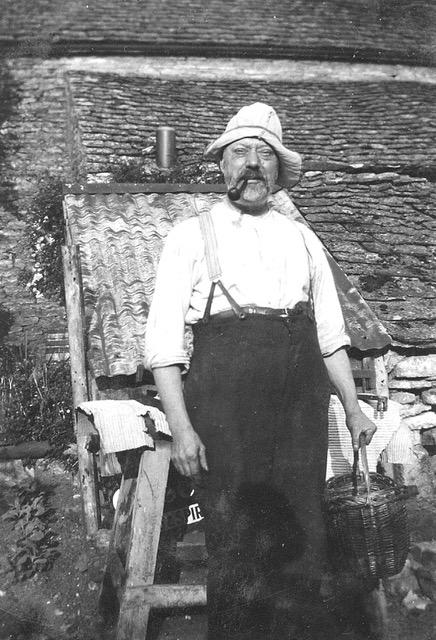

Arthur in his tobacco garden, considerably older than previous image.

Arthur retired in 1936. Most of his family had left home, but he kept up all his joining and other activities. He liked routine: all his working life he had had to get up at 6 am, six days a week, and finish when his boss said he could go home. One of his routines in retirement was to have his dinner at home about midday, walk to the allotment, start walking back, stop at the Greyhound for a quick half pint, and stroll home for his tea. One afternoon early in 1938 he wasn’t back at his usual time, and Grandma was getting worried. Then a neighbour came in and said, ‘Mrs Peters, I think your husband is lying on the pavement.’ She went to him, and he was dead. It was a sudden cardiac arrest that may have been connected with the condition that caused him to fail his army medical.

After he died, Grandma threw all his pipes away, but kept his tobacco jar as an ornament (on the piano top, of course). However, although Arthur hadn’t made a will, he had often told her that his other two smokers’ requisites, his lighter and his portable tobacco box, were to be left to his eldest son’s eldest son. In those days, everyone smoked, including the Queen, and men who worked with metal often carried a box like that – they still did when I was lecturing shop stewards from the aerospace industry in the late 1960s.

The tobacco jar, the lighter and the tobacco box left by Arthur Peters

There was a problem with the legacy: Arthur’s eldest son, Frank (my father), was married but had no children, though Arthur already had four grandchildren by his daughters. My mother, Edith, was pregnant when Arthur died. However, she had had a miscarriage in 1937 and they had chosen not to tell the family until they thought all danger was past.

Arthur had decided that if there was no eldest son of his eldest son his heirloom should go to one of his daughters, the mother of the second eldest grandchild, for life (Arthur, the eldest one, lived in New Zealand, and never visited England). If Frank had no son, she could leave it to anyone. Why he decided this arrangement I had no idea, but for most of my life I have known that my heirloom was sitting on my Auntie Laura’s mantelpiece.

When Grandma died in 1952 Mother was given the tobacco jar, which she had always admired. At that time it had a massive cork plug, but at some time in the last century it disintegrated. When Mother died I inherited the jar.

I was born a few months after Grandpa died. On 30 July 2022 I inherited my heirloom and was able to reunite the set.

Stroud Auctions valued the jar years ago, said it wasn’t worth much, and that it wasn’t meant to be a tobacco jar, just an ornament. Grandpa had added the plug. He was very good at making and repairing his gadgets. The EVVA table lighter is a bought gadget, an item from 1921 of the early attempt to rebuild German industry after the first world war. EVVA is now a manufacturer of mechanical and electronic locking systems.

The part of the heirloom that intrigues me is the pocket tobacco box, always known in the family as Arthur’s masterpiece, made to celebrate the end of his apprenticeship. The lid shows two churchwarden pipes, used a lot for a single smoke or for one session in the pub before the first world war, when cigarettes first became popular. Around the pipes is his address, from when he lived at home with his mother and father. This was, of course, before he married Amy and moved to Highgrove. That makes sense. But the lid also has the date, which doesn’t fit, of 1905. That was when Frank, his eldest son, was born. I believe he must have invented the scheme then, and added the date to the lid.

The tobacco box with Arthur Peters’ name, his address – The Thatched House, Shipton Moyne and the date, 1905.

John Peters (pictured extreme right) gave a talk based an this article at Stonehouse History Group’s meeting on February 8th 2023. The meeting featured short talks by the five speakers above.